Book review | On Beauty: The Cinema of Sanjay Leela Bhansali vociferously defends the filmmaker’s aesthetic

Is there anything that can be described as the Sanjay Leela Bhansali aesthetic? Is it the tawaif bathing in the perfume of unrequited love? Is it Aishwarya Rai sprinting across a stately mansion with her flaming dupatta chasing behind her? Or is it Rajput women descending into fire to escape the claws of a ravenous invader? Is it the long shot, play with words, Deepika Padukone’s moist eyes, or a hark back to the K Asif-Kamal Amrohi era? In his debut book, On Beauty: The Cinema of Sanjay Leela Bhansali, Prathyush Parasuraman argues that it’s all of the above – and so much more.

For Bhansali, beauty isn’t garnishing, but the plat principal, the main dish. It’s not a packaging, but the package itself. Not sone pe suhaga, but gleaming, glittering gold itself. It’s the story, not how he tells the story. Plot, to him, is secondary. No scene, or even shot, passes muster sans the beauty check. Yet Bhansali’s cinema is, more often than not, critiqued with a disclaimer tagging along – “But the costumes and sets were gorgeous.” Prathyush argues why that’s a footnote, and not the primary takeaway itself. For what’s cinema without its living, breathing, pulsating beauty? It’s a painting with a beating heart, but it has to be showcased on the canvas first.

Beauty trumps all

Prathyush throws a light on this fatal flaw in film critique – and film journalism at large. As the chatter becomes more trade-driven and tracking box office figures has turned into a spectator sport, film critique is also getting infiltrated by this unwarranted need to distill cinema through the sieve of objectivity. Although I disagree with the author that beauty permeates most frames of Bhansali’s cinema, there’s surely a poetry at play that doesn’t get its due. Too many critics are waxing eloquent about what a film made them think, instead of what it made them feel. The reception of cinema, especially that of Bhansali, is a “visceral intuition” instead of a “cerebral construction,” Prathyush puts it aptly.

But how much beauty is too much beauty? Prathyush begins his defense with a detailed, fly-on-the-wall anecdote from the eve of the release of inarguably Bhansali’s biggest commercial failure yet – Saawariya (2007). The filmmaker’s confidence, to go all Bobby like idol Raj Kapoor and launch two newcomers in a brave new world, stemmed from his unprecedented ability to pull off a songless, colourless Black after the grand and gilded Devdas. While the Amitabh Bachchan and Rani Mukerji-starrer became a critical masterpiece, Devdas caught the world’s imagination with its premiere at Cannes. Saawariya then had to do something for Bhansali – but he wouldn’t have predicted that it would turn out to be the biggest blow, despite launching a formidable future superstar in Ranbir Kapoor.

Saawariya is a fair microcosm of Bhansali’s cinema – a world where several worlds collide and confluence, a sex worker as narrator, a love triangle with two star-crossed lovers and the art of letting go, and songs staged with a fine blend of grandeur and intimacy. Yet the audience just didn’t get it. Sure, there’s beauty, but where’s the story? So Bhansali painstakingly crafted the screenplay for his next, Guzaarish (2010), and replaced newcomers with A-list stars – Hrithik Roshan and Aishwarya Rai. It was a safer risk than Saawariya probably, yet a riotous rebellion nonetheless – casting Hrithik and Aishwarya as a wheelchair-bound paraplegetic and his caretaker respectively, completely departing from their previous poles-apart yet star-gazy turns in Dhoom 2 (2006) and Jodhaa Akbar (2008). This one didn’t hit the mark either.

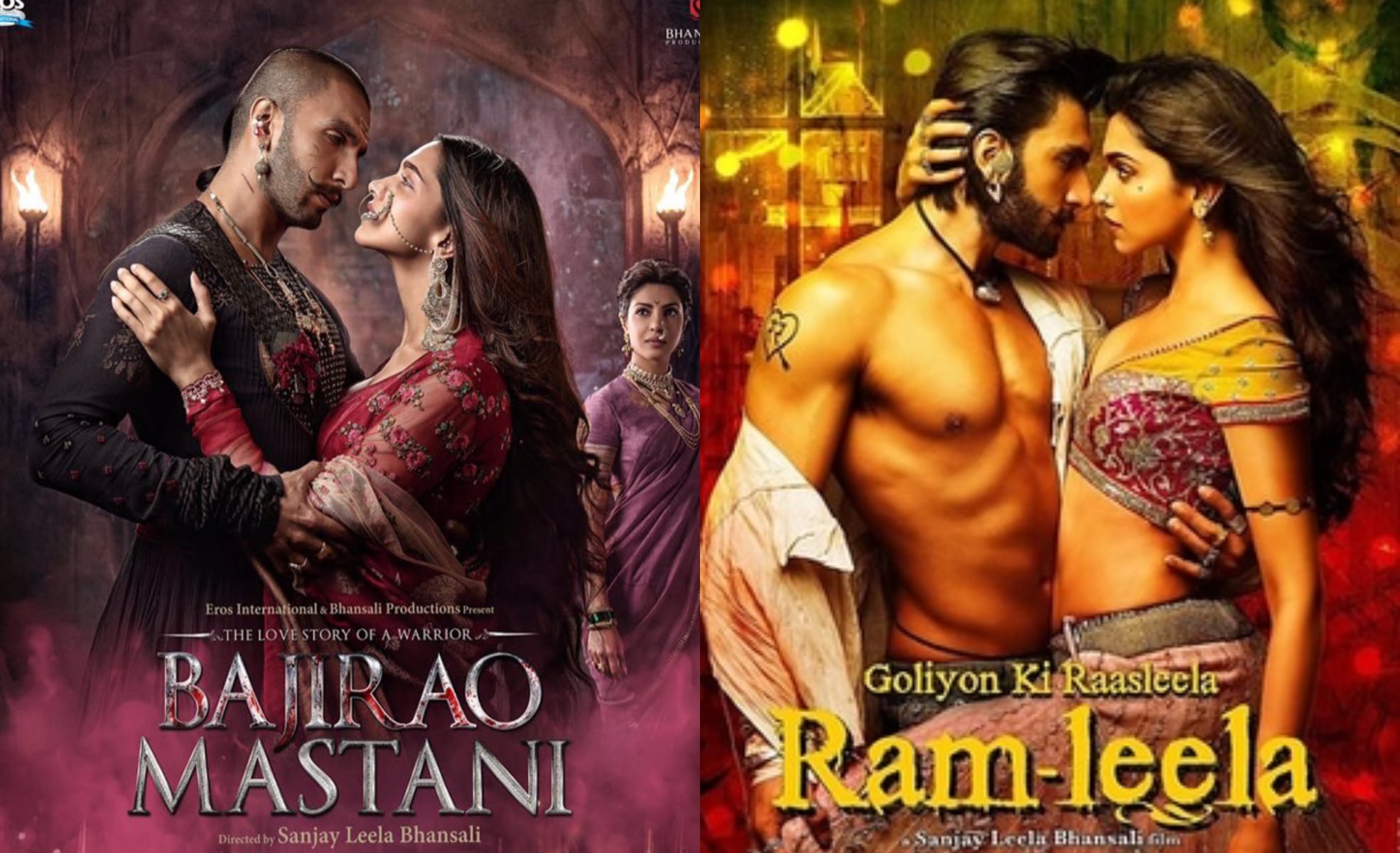

But like Vishal Bhardwaj, who has barely delivered any blockbusters in his two-decade-long-plus directorial career, Bhansali forges on – keeping his choices and sensibilities intact. Of course, he slashes and burns his world in every film – going from the red hues of Devdas to the monochromatic Black to the dowsed-in-blue Saawariya to the kaleidoscopic pleasures of Goliyon Ki Raasleela: Ram-Leela. But his priority remains beauty – aesthetic, mood, colour palette may change, but beauty must persist. Even after he secured a hit with Ram-Leela (2013), and repeated its leads in Bajirao Mastani (2015) and Padmaavat (2018), something shifted in their dynamic – dying together in Ram-Leela, dying apart in Bajirao Mastani, to dying because of the other in Padmaavat – all the while when the actors began dating, got engaged, and and were about to get married in real life.

Ironies like these also lend a beautiful undercurrent to Bhansali’s cinema. For his choice to go big and beautiful also emanates from irony. The filmmaker spent his childhood near Kamathipura, a red-light area in Mumbai, living inside a chawl. Naturally, his imagination would run wild. Watching cinematic masterpieces like Mughal-e-Azam (!960) and Pakeezah (1972) multiple times further fuelled his flights of fancy. The film set today is not only his playground, but also his right to design his land, his home, his world – the ones he never had – the way he always wanted to. Mostly dressed in black, the filmmaker can’t imagine the world he creates without colour. There’s ample room for scale and glamour, yet somewhere, the trials and tribulations come in the way, often making his creations more fuller and finer.

Prathyush touches upon these in a chapter titled “Violence in Beauty, Violence as Beauty in Ram-Leela.” Bhansali hasn’t shied away from violence – both emotional and physical – but that’s closely tied to his inevitable penchant for beauty. Yet the violence doesn’t seem glorified – the scars are beautiful, not so much the perverse streak to tear them wide open. Lovers hitting each other in Devdas; teacher bullying student in Black; a physically challenged man venting his frustration on his caretaker in Guzaarish; mother breaking daughter’s finger in Ram-Leela, women walking into fire with pride in Padmaavat, a nosepin piercing through a girl’s nose in Gangubai Kathiawadi, and a brothel madam lying down for a gangrape – these aren’t conventionally ‘beautiful’ elements for Hindi cinema, yet Bhansali brandishes them as his weapons of aesthetic and narrative choice.

The singular voice throughout the book – with fleeting first- and second-hand quotes peppered all over – makes one wonder if Prathyush’s case would have enriched further from more concentrated inputs from the filmmaker’s inputs, or those of his close collaborators. The lack of visuals also pinches occasionally, given every paragraph alludes to a frame, a picture. Whether that was a legal hurdle or a creative call, it turns out to be a constraint for those not steeped in Bhansali’s cinema. Yet, like Bhansali, Prathyush marches on, gently yet thrustfully floating his words, thoughts, and arguments. Humour peeps into a few places (he calls the Rajput women heading for jauhar ‘suicide squad’), forced but instructive alliteration (“baroque, blinding brilliance”) creeps in somewhere else. With all its fissures and abiding flair, Prathyush’s book, like its subject, is a thing of beauty, a joy forever.

On Beauty: The Cinema of Sanjay Leela Bhansali is published by Penguin Random House.